Christopher Columbus’ Eclipse, 1504 CE

After a long trip to the Americas in 1503 CE, in his fourth voyage, Columbus was stranded on the island of Jamaica. In principle, he managed to obtain provisions from the Caciques natives in exchange for some trinkets and rubbish. As the months went by, novelty and hospitality started to decrease and also the sailors started to become aggressive with the natives to obtain food. Upset, the Indians communicated to the Spanish that they would not provide any more supplies.

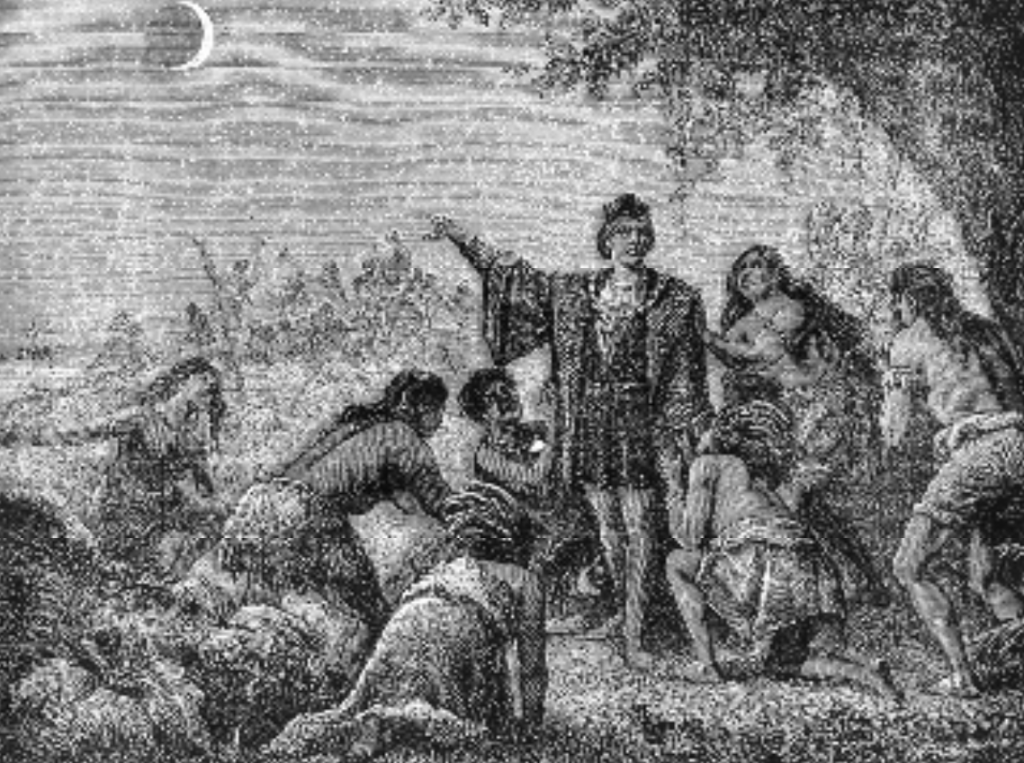

Fig. 1- Columbus impressing the natives. This illustration from Camille Flammarion’s Astronomie Populaire shows how Christopher Columbus used an eclipse of the Moon to assert his power over the Indians in Jamaica. Credit: © photo Jean-Loup Charmet.

Desperate with the threat of famine, Columbus came up with an ingenious plan. He checked his Calendarium, which contained predictions of lunar eclipses for several years. In particular, it predicted a total eclipse of the Moon on the Antilles on February 29, 1504 CE. That evening, Columbus invited the Caciques onboard his Capitana for a serious conversation. He told them that they were Christians and their God did not appreciate the way they had been treating them and would punish the Indians with famine and pestilence and, as a sign of dissatisfaction, he would darken the Moon.

As soon as he said that, the Earth’s shadow started to cover the white disk. Terrified, the natives begged Columbus to bring back the light. According to Ferdinand Columbus (second son of Christopher Columbus), cited by Sinnot (1992):

“The Indians observed this [the eclipse] and were so astonished and frightened that with great cries and lamentations they came running from all directions to the ships, carrying provisions and begging (…) and promising they would diligently supply all their needs in the future.”

He replied that he needed to consult his God. He shut himself in a cabin for nearly two hours. Just before the end of totality, he reappeared and announced that God had given his pardon, and would bring them back the Moon provided that the Christians were given provisions. Immediately, the Moon reappeared. Astonished, the natives provided Columbus and his crew their needed provisions until they were able to return to Europe.

The use of eclipses as a tool to manipulate populations less knowledgeable about eclipses is also present in diverse works of fiction. In 1889, Mark Twain published A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, a novel envisioning life in the sixth-century England. The author has Hank Morgan, the yankee in the title, hoodwinking the ignorant folk of that era by invoking prior knowledge of a solar eclipse on June 21, 528 CE. Twain has Morgan, who is jailed awaiting execution, threaten King Arthur with a blanking out of the Sun:

“Go back and tell the king that at that hour I will smother the whole world in the dead blackness of midnight; I will blot out the Sun, and he shall never shine again; the fruits of the Earth shall not rot for lack of light and warmth, and the peoples of the Earth shall famish and die, to the last man!”

The description provided by Twain is accurate in many senses, except for the fact that there was no solar eclipse at all visible in England in 528 CE. There are more examples of this theme in literature, such as The Adventures of Tintin by Georges Remi and King Solomon’s Mines by H. Rider Haggard.

Cartographic Eclipse, 1706 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1701-1800/1706-05-12.gif

This eclipse was of high interest to scientific geographers who relied on astronomical calculations to produce terrestrial maps. The moment of the eclipse became a cartographic point of reference, so that maps represented the world as it was in 1706 CE.

From the tops of the Swiss mountains, at Montpellier, and other places in Europe, several stars were observable at the naked eye at the time of full moon, such as the Aldebaran and Capella, as well as the planets Venus, Mercury and Saturn.

This eclipse caused great commotion. It is said that at Geneva the Council was compelled to close their deliberations, as they could see neither to read nor write. In several places people prostrated on the ground and prayed, wondering the Day of Judgment had come.

Animals are also sensitive to these changes in the sky. Actually, in that day bats were flying, fowls and pigeons flew hastily to their roots, cage-birds become silent, hiding their heads under their wings, and animals at labor in the fields stood still.

Edmond Halley’s Eclipse, 1715 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1701-1800/1715-05-03.gif

“A few seconds before the Sun was all hid, there discovered itself round the Moon a luminous ring about a digit, or perhaps a tenth part of the Moon’s diameter, in breadth. It was of a pale whiteness, or rather pearl-color, seeming to me a little tinged with the colors of the iris, and to be concentric with the Moon.” – Edmond Halley

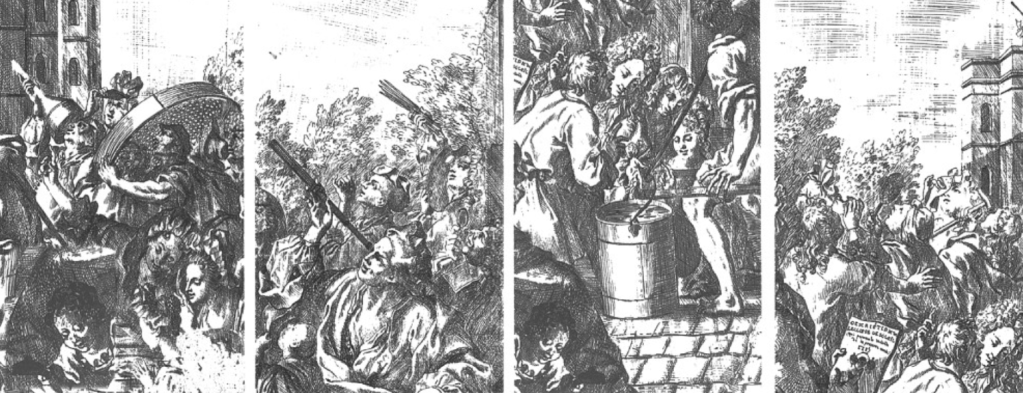

Fig. 2 – The solar eclipse of 1715. Visible as partial at Paris, it provided the chance to observe the event in various ways: directly through telescopes, smoked glass, pinholes, sieves, and various filters, or indirectly by reflection in a bucket of water. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF).

This was the poetic, inspirational description of the British astronomer Edmond Halley (1656-1742 CE) for the solar corona during the total solar eclipse of April 3, 1715 CE, visible in England and Wales. The King of France and some of the royal family of England should have also had observed the eclipse.

Halley became famous for discovering the periodicity of certain comets and predicting their return, such as the comet he had observed in 1682 and calculated to return after 76 years, and which was named after him. Basing his calculations on the law of universal attraction by Newton, he provided the first physical explanation for the appearance of these wandering bodies that had previously terrified people.

Banneker’s Eclipse, 1731 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1701-1800/1790-04-14.gif

Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806 CE) is the first Black American scientist of note. Born free on November 9, 1731 CE, he was son to Robert, a slave from Guinea, West Africa, and to his free wife Mary Banneky, of English-African descent. At that time, it was rare for Black people to be born free, but that occurred because his mother was a free woman.

As a child, he was very curious: he enjoyed numbers, and learning how things worked. One of his first significant projects was to build his own clock. One day, a friend showed him a pocket watch. Benjamin was so fascinated that he decided to make his own. After two years of work he had a totally wooden- made clock!

Despite working hard to support his family, Banneker had eight years of schooling from a Quaker teacher at an integrated private academy. He borrowed and read books by Addison, Pope, Shakespeare, Milton, and Dryden, studied the stars, and created and solved math puzzles as both entertainment and self- education.

Unarguably, his most remarkable accomplishment has been to accurately predict the solar eclipse of April 14, 1789 CE. Other famous scientists of the time disbelieved Banneker’s prediction, as they had their own dates; but as the Sun was partially being covered on April 14, 1789 CE, Benjamin Banneker’ ‘star’ began to shine!

Banneker is a brilliant example of a scientist who fought against socioeconomic and ethnical constraints, as well as social class determinants for Black researchers at the time, showing that barriers can and should be overcome and giving important contributions to Astronomy.

Nat Turner’s Eclipse, 1831 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1801-1900/1831-02-12.gif

The greatest slave revolt in North America was led by Nat Turner (1800- 1831 CE). Very clever, Turner learned how to read with his masters’ son – an undesirable skill from the masters’ viewpoint for a slave during these times due to fear of rebellion. Turner, afterwards, dedicated himself to religion and became a preacher for his followers.

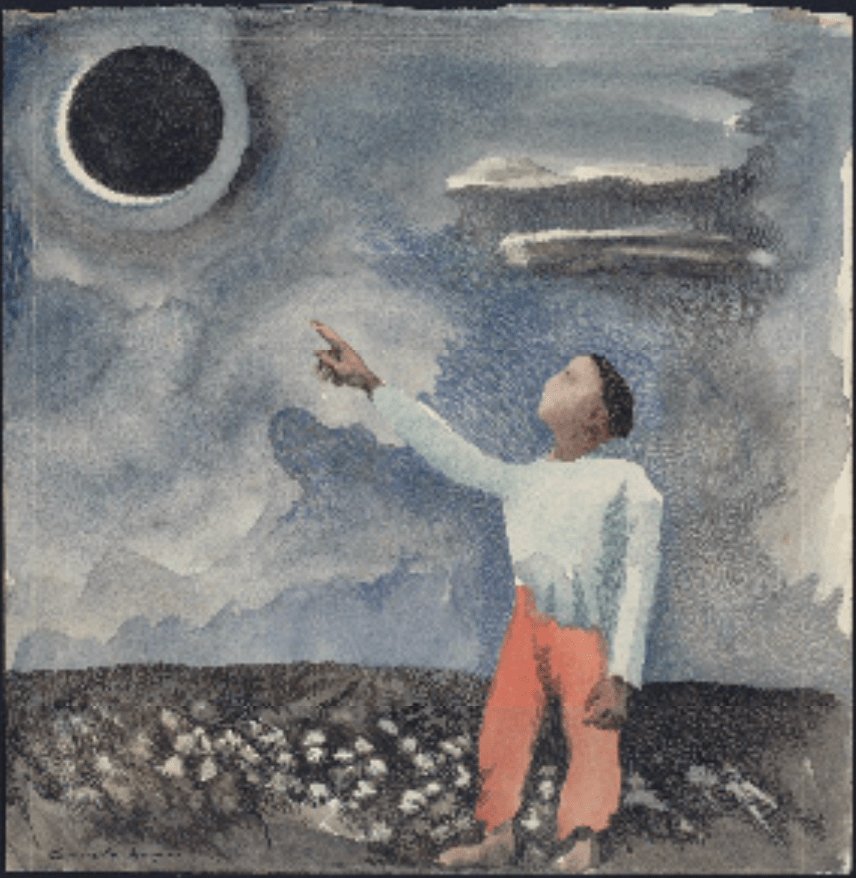

Fig. 3 – Nat Turner points at a lunar eclipse. He foresees the rebellion that would take place with the eclipsed Moon. Credit: Bernarda Bryson.

In 1828 CE, he had a vision: he would lead his people to liberty, but he should wait for a sign from God – and it came from the sky. An annular eclipse of the Sun occurred on February 12, 1831 CE. Turner interpreted it as a ‘black angel’ occulting a white one – the time had arrived for blacks to overcome whites, so the time had come for rebellion.

Several months later, after having murdered his original masters, Turner and his band of insurgents headed for the small town of Jerusalem where militiamen promptly interrupted their march. Most of the slaves, including Turner, went into hiding for seventy days before being taken to the gallows and hanged.

Many people died during this revolt, and in no other episode in American history have a so large number of slave owners perished, a reason why Turner is considered a hero of the resistance to oppression against black people in the United States.

Adams’ Eclipse, 1851 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1801-1900/1831-02-12.gif

The total solar eclipse of July 28, 1851 CE, was the first subject of an eclipse expedition. The total phase was visible in Norway and Sweden, and many astronomers from all parts of Europe traveled to those countries to observe the eclipse.

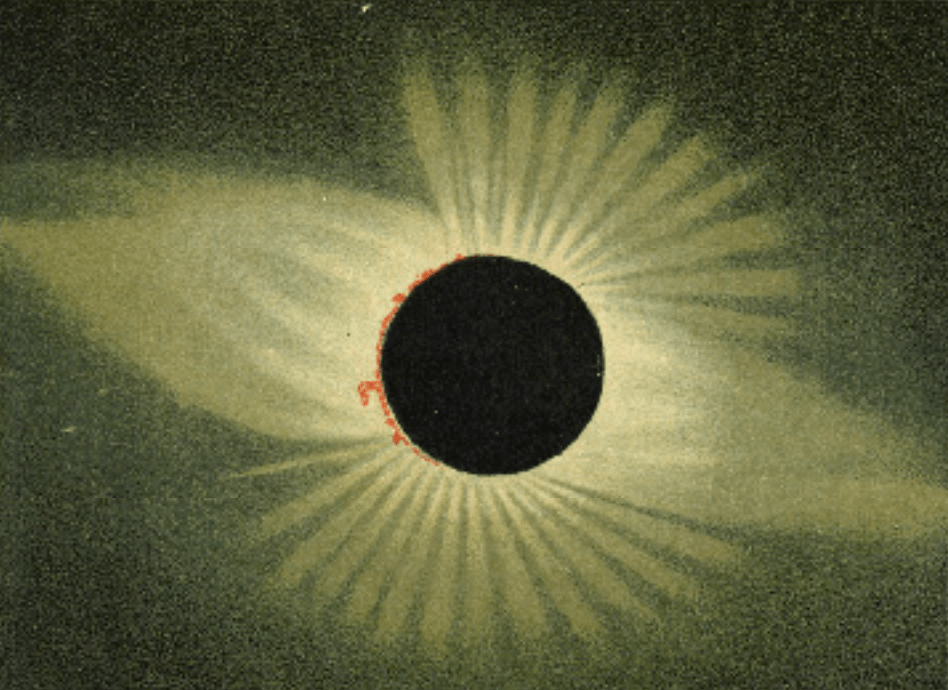

Red flames were in evidence, and the fact that they belonged to the Sun and not to the Moon was clearly established. The first photograph of the solar corona was taken during this solar eclipse and the best observations were made in Scandinavia. Edwin Dunkin wrote:

“The prominences were clearly visible, especially a large hooked protuberance. This remarkable stream of hydrogen gas, rendered incandescent while passing through the heated photosphere of the Sun, attracted the attention of nearly all the observers at the different stations.”

The best account comes from the brilliant astronomer John Couch Adams. In 1845 CE, he calculated, at the same time as the Frenchman Le Verrier, the position of Neptune. At this time in history, many astronomers had never observed a total eclipse, because these phenomena rarely occurred at any given place, and transport facilities were few and far between.

In his inspirational article that appeared in the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, Adams’ lyrical style conveys the extraordinary emotion of an experienced astronomer who realizes that he is a complete novice in the arts of observing this spectacle for the first time:

“The approach of the total eclipse of July 28, 1851, produced in me a strong desire to witness so rare and striking a phenomenon. Not that I had much hope of being able to add anything of scientific importance to the accounts of the many experienced astronomers who were preparing to observe it; for I was not unaware of the difficulty which one not much accustomed to astronomical observation would have in preserving the requisite coolness and command of the attention amid circumstances so novel, where the points of interest are so numerous, and the time allowed for observation is so short.”

Adams then describes the awe-inspiring, magical appearance of the corona:

“The appearance of the corona, shining with a cold unEarthly light, made an impression on my mind which can never be effaced, and an involuntary feeling of loneliness and disquietude came upon me… A party of haymakers, who had been laughing and chatting merrily at their work during the early part of the eclipse, were now seated on the ground, in a group near the telescope, watching what was taking place with the greatest interest, and preserving a profound silence… A crow was the only animal near me; it seemed quite bewildered, croaking and flying backwards and forwards near the ground in an uncertain manner.”

In another written piece, he compares the corona with the luminous halo that painters draw around the heads of saints.

General Gordon Fatal Eclipses, 1863 and 1885 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1801-1900/1885-03-16.gif

An ancient Chinese aphorism says that every dynasty starts with the replacement of an old, degenerate regime ruled by corruption and ineffectiveness. Nevertheless, as time goes by, new governors, in principle virtuous, come into the same vices and the so-called “Mandate of Heaven” (as they reign by divine gift) is passed on.

In such a society, signs of the sky can significantly influence politics. The Ch’ing dynasty began in 1644 CE, and achieved great splendor. By the mid-19th century, however, it started to become ineffective and corrupt.

At this time, the British general Charles Gordon was charged by the western powers to help the Emperor of China and his dynasty in their fight against the Taiping revolt. Skilled with military genius and leadership, Gordon commanded an army of Chinese mercenaries and had many victories.

On November 25, 1863 CE, a partial eclipse of the Moon frightened his troops during the siege of Soochow (Suzhou) in Kiangsu (Jiangsu). The superstitious Chinese interpreted the event as a bad omen for the Emperor. Soochow was not conquered and the Taiping revolt was settled peacefully. This eclipse was thus the cause of General Gordon’s first defeat.

Another eclipse, solar this time, on March 16, demoralized Gordon’s troops and was directly responsible for his death. In 1885 CE, he was in charge of the defense of Khartoum, the capital of the Sudan, under attack by a charismatic religious leader, the Mahdi. A solar eclipse demoralized Gordon’s troops. The city was taken before British troops could arrive with reinforcements and the British general did not survive the massacre.

The Great Eclipse of 1878

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1801-1900/1878-07-29.gif

Considered one of the greatest eclipse events of that century, it is known as the great eclipse of 1878 CE for its large path of visibility. The Moon’s shadow took some 20 minutes to cross Wyoming and Colorado, in the United States, on July 29, 1878 CE. Many tourists filled hotels to see the spectacle – even the famous inventor Thomas Edison was there!

Extensive preparations were made by officers in charge of the National Observatory to observe the eclipse. Five expeditions were assigned to observe the phenomenon and conduct relevant scientific investigations, such as making drawings of the corona, and to study the physical constitution of the Sun. Although the corona was photographed in 1851 CE, the results were not satisfactory and, in 1878, drawings provided the best information about its size and shape.

Fig. 4 – Capturing the corona. Magnificent pastel drawing by E.L. Trouvelot of the total eclipse of Sun’s corona during the May 29, 1878 eclipse. Credit: American expedition to Wyoming; from the E.L. Trouvelot, Meudon Collection.

The 1878 eclipse was observed by the American astronomer Maria Mitchell, the first woman astronomer to join the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She led a team of five of her female students on a cross-country journey to Denver, Colorado, to observe and scientifically report a total solar eclipse. They traveled by train at a time when ladies did not travel unescorted. Her students were fascinated with the trip, although a little frightened.

Maria took care of all the logistics of sending telescopes to an observational site and gave each student instructions, telling them the observations they should make.

Fig. 5 – Maria Mitchell. Image courtesy of the Maria Mitchell Association. Source: Pocantico Hills Central School Web site, https://www.pocanticohills.org/

“You will see Nature as you never saw it before – it will neither be day nor night – open your senses to all the revelations”, she pointed out.

“Let your eyes take note of the colors of Earth and Sky. Observe the tint of the Sun. Look for a gleam of light in the horizon. Notice the color of the foliage. Use another sense – notice if flowers give forth the odors of evening. Listen if the animals show signs of fear – if the dog barks – if the owl shrieks – if the birds cease to sing – if the bee ceases its hum – if the butterfly stops its flight – it is said that even the ant pauses with its burden and no longer gives the lesson to the sluggard.”

She described also the most glorious moment, that is, the observation of the corona!

“As the last rays of sunlight disappeared, the corona burst out all around the Sun, so intensely bright near the Sun that the eye could scarcely bear it; extending less dazzlingly bright around the Sun for the space of about half the Sun’s diameter, and in some directions sending off streamers for millions of miles…”

The young ladies were enthusiastic about the experience and harbored a brave attitude at a time when women were not supposed to be inside scientific circles. At an epoch when men’s colleges rarely engaged science students with direct field experience like this, Mitchell’s students were entering a new era of learning for women. This event represented significant scientific, societal, and pedagogical advancement promoted by a pioneering woman.

Eclipse of Lawrence of Arabia, 1917 CE

During the First World War, Thomas Edward Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia, advised the Arabs in their revolt against the Ottoman Empire. One of his greatest exploits was the capture of Aqaba, a fortified port on the Sinai Peninsula, with a small troop of 50 Bedouin.

Fig. 6 – Lawrence of Arabia. Credit: Public domain.

In the Seven Pillars of Wisdom, he reports a lunar eclipse in Egypt that helped him overcome the first defensive position, Kethira:

“By my diary there was an eclipse. Duly it came, and the Arabs forced the post without loss, while the superstitious soldiers were firing rifles and clanging copper pots to rescue the threatened satellite.”

Aqaba was taken a few days later. Thanks to this strategic port having fallen to the British, the Allies soon recaptured Jerusalem and Damascus. The Turkish soldiers had another reason to fear the eclipse: according to an Islamic tradition, the Day of the Last Judgment is linked to an eclipse in the middle of the month of Ramadan, and this was exactly the case on that date.

This is just one illustration of how eclipses through the centuries have been recurrently associated by different civilizations to prophecies of the end of the world. Indeed, even today there are people who do not feel very comfortable to observe the shining solar disk being occulted by the Moon, wondering that such event would represent far more than a mere astronomical event, and that there would not be tomorrow.

Einstein Eclipse, 1919 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1901-2000/1919-05-29.gif

This eclipse has definitively revolutionized the history of science in the twentieth century, as it helped to confirm the General Theory of Relativity by Albert Einstein (1879-1955 CE). Indeed, one of Einstein’s most remarkable contributions to science was his General Theory of Relativity (GTR), formulated between 1913 and 1916 CE. This theory contradicted Newton’s and provided fundamental new understandings of time and space measurement.

Fig. 7 – Total solar eclipse in Sobral, Brazil, 1919. The large city of Sobral in Ceara, Brazil, as it was in 1919 (left), and a recent monument to celebrate the eclipse (right). Source: Sociedade Brasileira de Fisica Web site, https://www.sbfisica.org.br/v1/sbf/

GTR was extremelyy complex to understand though and, in order to be accepted, it was necessary that Einstein’s theory predicted or explained some observed phenomenon that the Newtonian theory could not.

In this scenario, Eddington came up with the idea that a total eclipse of the Sun would provide such a unique opportunity to quantitatively test Einstein’s theory. How? If it were correct, the light from stars would be bent by the strong gravitational field of the Sun. And what circumstance was necessary to observe this? Totality and stars appearing close-by because the test required several bright stars close to the limb of the Sun during the eclipse. The eclipse of May 29, 1919, offered such conditions.

The path of totality crossed Brazil, in South America, and Principe, an island owned by Portugal in the Gulf of Guinea, just to the north of the equator and 150 miles from the African coast. In northeastern Brazil, the city of Sobral, Ceara state, was the best post of observation of the phenomenon and two expeditions of American and English scientists joined the Brazilians to observe the eclipse.

Their purposes were distinct. The Brazilian commission focused on studies of the solar corona, its form and shape, and performed spectroscopic analysis of its constitution. The American and English intended to verify experimentally the consequences of GTR.

After analysis of the eclipse results, the royal astronomer Frank Dyson announced, in November 1919 CE, that the results confirmed the theory and it was made public: Einstein was right! In fact, what provoked such commotion was precise measurement of the deviation of starlight passing close to the Sun. The value of such deviation agreed with the prediction of Einstein’s GTR (1.75 arc seconds), but was almost double the value predicted by Newton’s gravitational theory (0.87 arc seconds).

This is one of the most dramatic events in the history of science and was front-page news around the globe. The London Times featured the headlines, “Revolution in science. New theory of the universe. Newtonian ideas overthrown” and The Washington Post, with “New theory of space: has no absolute dimensions, nor has time, say Savants.” The president of the Royal Society, J J Thomson, described the general theory as “the greatest discovery in connection with gravitation since Newton… Our conceptions of the fabric of the universe must be fundamentally altered.”

Although people were still mystified by Einstein’s theory, his worldwide popularity as a legendary scientist increased exponentially almost overnight thanks partly to the fanfare that followed the eclipse. Einstein was also very charismatic and became famous for his equation E=mc2.

Eclipse of End of Millennium, 1999 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/1901-2000/1999-08-11.gif

The eclipse of August 11, 1999 CE, was eagerly awaited and witnessed for millions of people, many having traveled around to see the show. It covered the Atlantic near Newfoundland, and the path of totality proceeded eastwards to the southwestern tip of England. The Moon’s shadow then crossed France, Germany, several eastern European countries, Turkey, the Middle East, Pakistan, and India, before eventually reaching the Bay of Bengal.

Stories about the end of the world have always frightened people throughout history. An eclipse of the Sun in the last year of the millennium would be the perfect scenario for consternation about this issue. One key ingredient for this eclipse was related to the forthcoming millennium, including predictions of catastrophes.

First Eclipses of the Third Millennium, 2001 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/2001-2100/2001-06-21.gif

There were two eclipses opening the Third Millennium: a lunar and a solar one. The first happened on January 9, 2001 CE, and was lunar. That was total as viewed from most of Asia, Africa, Europe, and the eastern seaboard of North America.

In Nigeria, the eclipse caused great commotion, and its advent was blamed on sinners. In the northeastern part of the country, there were rampages by gangs of youths. Similar destruction occurred in other towns.

“The immoral acts committed in these places are responsible for this eclipse,”

explained one of the leaders of the riots.

Five months later, on June 21, 2001 CE, the first total solar eclipse of the millennium was also witnessed in Africa. As the track passed over Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and finally the southern part of the island of Madagascar, thousands of tourists and millions of local inhabitants watched the spectacle.

Elsewhere wailing and gnashing of teeth accompanied what was considered the “rooting of the Sun,” from which the world would not recover. The world did recover quite promptly, and we keep on waiting for the next meeting between our two closest celestial bodies in their marvelous space ballet.

Eclipse seen from space, 2006 CE

See Visibility Map: http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/5MCSEmap/2001-2100/2006-03-29.gif

In Africa, many regard eclipses not simple astronomical phenomena, but attribute some metaphysical meaning to them, usually related to prophecies of the end of the world.

In the countdown to the 29 March eclipse, for example, an Islamic “scholar”, a Mallam Muniru Hamidu, declared that the world was going to end because it is written in the Qur’an that when the end of the world got nigh, “God would cause the sun and the moon to come together”. Other religious books such as the Christian Bible connects eclipses with facts such as the Final Judgment. One of the signs is the descent of darkness in the daytime.

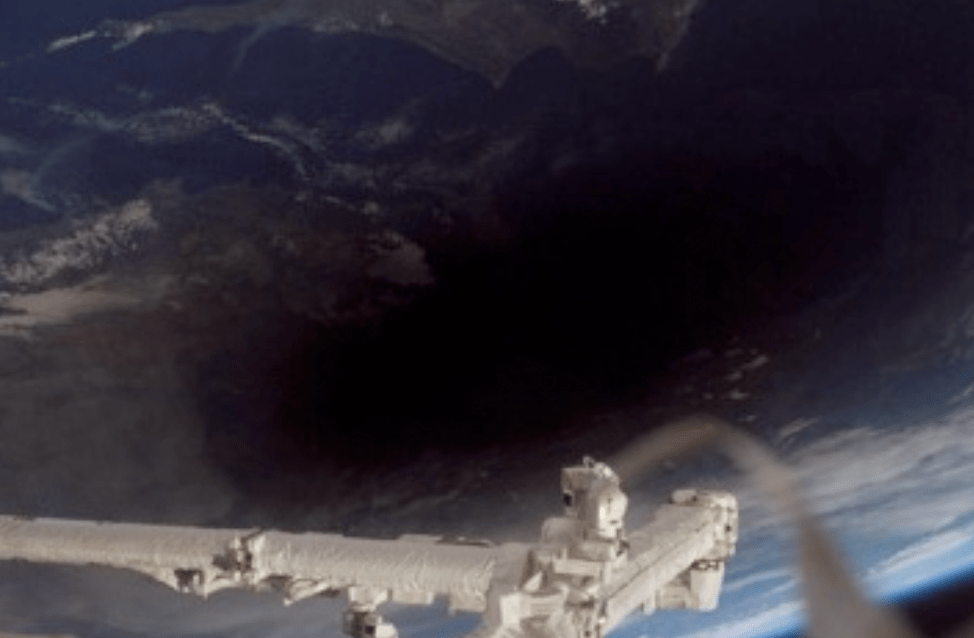

Fig. 8 – Eclipse in outer space. The Moon’s shadow passing over the Earth during eclipse. Source: NASA.

The image below, obtained from the International Space Station, 230 miles above the planet, was positioned to view the umbral shadow cast by the Moon as it moved between the Sun and Earth during the solar eclipse on March 29, 2006 CE. The astronaut image captures the umbral shadow across southern Turkey, northern Cyprus, and the Mediterranean Sea. People living in these regions observed a total solar eclipse in which the Moon completely covered the Sun’s disk.